Angioedema: enfoque diagnóstico y terapéutico

Palabras clave:

Angioedema, urticaria, angioedema hereditarioResumen

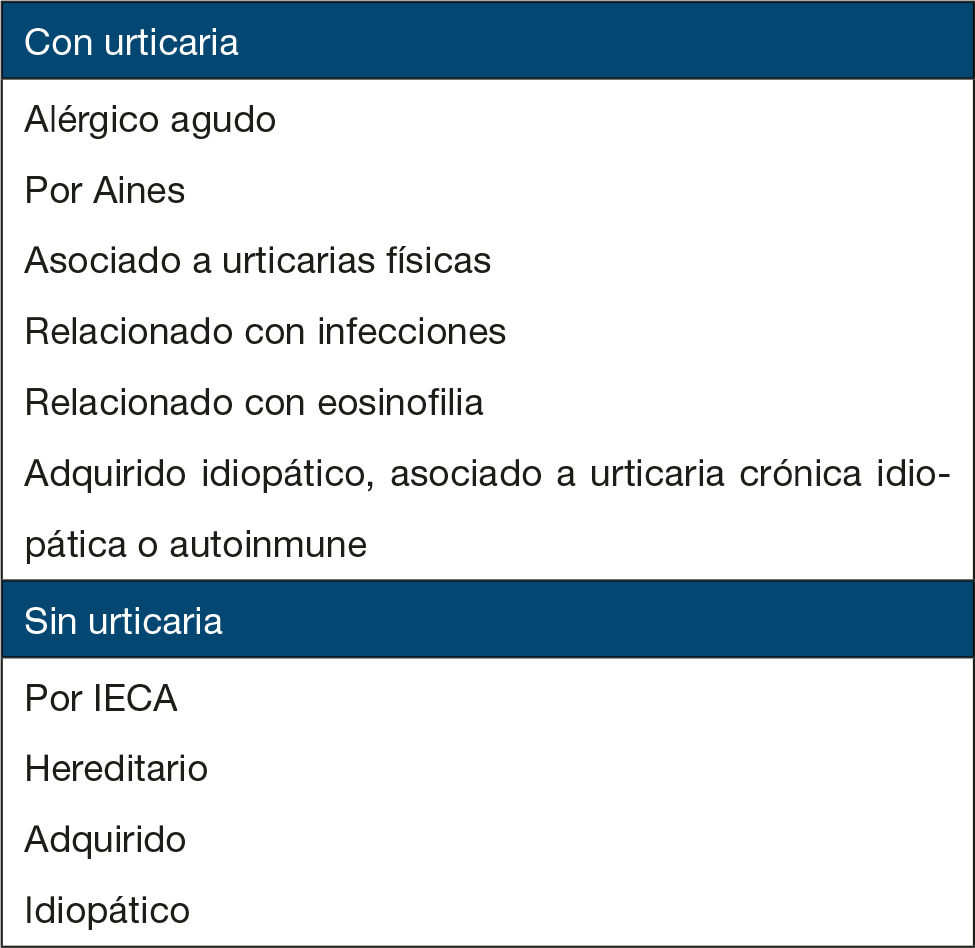

A pesar de haber sido descubierto el angioenema hace más de cien años, su origen, su fisiopatología y el tratamiento de sus diferentes tipos son mal entendidos por la mayoría de los médicos. El angioedema puede ser causado por una activación en la formación de cininas o por degranulación de mastocitos. El angioedema inducido por los inhibidores de la enzima convertidora de angiotensina es producido por la inhibición de la degradación enzimática de la bradicinina. El angioedema puede ser ocasionado por una variedad de antiinflamatorios no esteroideos, siendo más común por la aspirina. A menudo el angioedema adquirido idiopático es recurrente y crónico, asociado normalmente a urticaria. Su nombre implica que habitualmente no puede ser atribuido a una causa identificable. El angioedema hereditario es una patología caracterizada por episodios repetidos de edema que afectan la piel y las mucosas de las vías respiratorias superiores y

del tubo digestivo, debido a un déficit o disfunción del inhibidor de la C1 esterasa. Tiene carácter hereditario con una transmisión autosómica dominante. Recientemente varios grupos han reportado una tercera forma de angioedema hereditario que ocurre exclusivamente en mujeres con una actividad funcional y cuantitativa normal del inhibidor de C1 relacionada con los estrógenos. El angioedema adquirido ha sido descrito en pacientes con linfoma que tienen niveles disminuidos del inhibidor de C1 o autoanticuerpos dirigidos contra tal proteína.

Biografía del autor/a

Ricardo Cardona

Alergólogo Clínico, Magíster en Inmunología, Coordinador de la Especialidad en Alergología Clínica, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Antioquia. Medellín_ Colombia.

Liliana Tamayo

Dermatóloga, Docente de Alergología Clínica, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Antioquia. Medellín_ Colombia.

Mauricio Fernando Escobar

Residente de II año de la Especialidad en Alergología Clínica, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Antioquia. Medellín_ Colombia

Referencias bibliográficas

2. Miyagawa S, Takahashi Y, Nagai A, Yamamoto Y, Nakagawa A, Hori K, et al. Angio-oedema in a neonate with IgG antibodies to parvovirus B19 following intrauterine parvovirus B19 infection. The British Journal of Dermatology. 2000;143:428-30.

3. Kidd JM, 3rd, Cohen SH, Sosman AJ, Fink JN. Fooddependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1983; 71:407-11.

4. Sánchez-Borges M, Capriles-Hulett A, Caballero-Fonseca F. NSAID-Induced Urticaria and Angioedema. A Reappraisal of its Clinical Management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002; 3:599-607.

5. Sanchez-Borges M, Capriles-Hulett A. Atopy is a risk factor for non-steroidal anti-infl ammatory drug sensitivity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000; 84:101-6.

6. Smith WL, Dewitt DL. Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases-1 and -2. Advances in immunology. 1996; 62:167-215.

7. Pennisi E. Building a better aspirin. Science (New York, NY. 1998 May 22; 280:1191-2.

8. Quaratino D, Romano A, Di Fonso M, Papa G, Perrone MR, D’Ambrosio FP, et al. Tolerability of meloxicam in patients with histories of adverse reactions to nonsteroidal anti-infl ammatory drugs. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000; 84:613-7.

9. Bavbek S, Celik G, Ediger D, Mungan D, Demirel YS, Misirligil Z. The use of nimesulide in patients with acetylsalicylic acid and nonsteroidal anti-infl ammatory drug intolerance. J Asthma. 1999; 36: 657-63.

10. Crouch T, Stafford C. Urticaria associated with COX-2 inhibitors. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2000 ; 84:38.

11. May A, Weber A, Gall H, Kaufmann R, Zollner TM. Means of increasing sensitivity of an in vitro diagnostic test for aspirin intolerance. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999; 29:1402-11.

12. Sánchez Borges M, Capriles-Hulett A, Caballero-Fonseca F, Perez CR. Tolerability to new COX-2 inhibitors in NSAID-sensitive patients with cutaneous reactions. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001; 87:201-4.

13. Asero R. Leukotriene receptor antagonists may prevent NSAID-induced exacerbations in patients with chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000; 85:156-7.

14. Wanderer AA, Hoffman HM. The spectrum of acquired and familial cold-induced urticaria/urticaria-like syndromes. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America. 2004; 24:259-86, vii.

15. Dice JP. Physical urticaria. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America. 2004; 24: 225-46, vi.

16. Weidenbach H, Beckh KH, Lerch MM, Adler G. Precipitation of hereditary angioedema by infectious mononucleosis. Lancet. 1993; 342:934.

17. Rais M, Unzeitig J, Grant JA. Refractory exacerbations of hereditary angioedema with associated Helicobacter pylori infection. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1999; 103: 713-4.

18. Farkas H, Fust G, Fekete B, Karadi I, Varga L. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and improvement of hereditary angioneurotic oedema. Lancet. 2001; 358:1695-6.

19. Gleich GJ, Schroeter AL, Marcoux JP, Sachs MI, O’Connell EJ, Kohler PF. Episodic angioedema associated with eosinophilia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1984; 310: 1621-6.

20. Tillie-Leblond I, Gosset P, Janin A, Salez F, Prin L, Tonnel AB. Increased interleukin-6 production during the acute phase of the syndrome of episodic angioedema and hypereosinophilia. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998; 28: 491-6.

21. Putterman C, Barak V, Caraco Y, Neuman T, Shalit M. Episodic angioedema with eosinophilia: a case associated with T cell activation and cytokine production. Annals of Allergy. 1993; 70: 243-8.

22. Butterfi eld JH, Leiferman KM, Abrams J, Silver JE, Bower J, Gonchoroff N; et al. Elevated serum levels of interleukin-5 in patients with the syndrome of episodic angioedema and eosinophilia. Blood. 1992; 79: 688-92.

23. Garcia-Abujeta JL, Martin-Gil D, Martin M, Lopez R, Suarez A, Rodriguez F., et al. Impaired type-1 activity and increased NK cells in Gleich’s syndrome. Allergy. 2001; 56: 1221-5.

24. Walsh GM, Sexton DW, Blaylock MG. Corticosteroids, eosinophils and bronchial epithelial cells: new insights into the resolution of infl ammation in asthma. The Journal of Endocrinology. 2003 Jul; 178: 37-43.

25. Sabroe RA, Seed PT, Francis DM, Barr RM, Black AK, Greaves MW. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: comparison of the clinical features of patients with and without anti-FcepsilonRI or anti-IgE autoantibodies. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1999; 40:443-50.

26. Hide M, Francis DM, Grattan CE, Hakimi J, Kochan JP, Greaves MW. Autoantibodies against the high-affi nity IgE receptor as a cause of histamine release in chronic urticaria. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1993; 328: 1599-604.

27. Fiebiger E, Maurer D, Holub H, Reininger B, Hartmann G, Woisetschlager M., et al. Serum IgG autoantibodies directed against the alpha chain of Fc epsilon RI: a selective marker and pathogenetic factor for a distinct subset of chronic urticaria patients? The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995; 96: 2606-12.

28. Ferrer M, Kinet JP, Kaplan AP. Comparative studies of functional and binding assays for IgG antiFc(epsilon)RIalpha (alpha-subunit) in chronic urticaria. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1998; 101: 672-6.

29. Rumbyrt JS, Schocket AL. Chronic urticaria and thyroid disease. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America. 2004; 24: 215-23, vi.

30. Claveau J, Lavoie A, Brunet C, Bedard PM, Hebert J. Comparison of histamine-releasing factor recovered from skin and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1996; 77: 475-9.

31. Confi no-Cohen R, Aharoni D, Goldberg A, Gurevitch I, Buchs A, Weiss M., et al. Evidence for aberrant regulation of the p21Ras pathway in PBMCs of patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2002; 109: 349-56.

32. Sabroe RA, Grattan CE, Francis DM, Barr RM, Kobza Black A, Greaves MW. The autologous serum skin test: a screening test for autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticaria. The British Journal of Dermatology. 1999; 140:446-52.

33. Grattan CE, Walpole D, Francis DM, Niimi N, Dootson G, Edler S., et al. Flow cytometric analysis of basophil numbers in chronic urticaria: basopenia is related to serum histamine releasing activity. Clin Exp Allergy. 1997; 27: 1417-24.

34. Kaplan AP. Clinical practice. Chronic urticaria and angioedema. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002; 346: 175-9.

35. Grattan CE, O’Donnell BF, Francis DM, Niimi N, Barlow RJ, Seed PT., et al. Randomized double-blind study of cyclosporin in chronic ‘idiopathic’ urticaria. The British Journal of Dermatology. 2000; 143: 365-72.

36. Gach JE, Sabroe RA, Greaves MW, Black AK. Methotrexate-responsive chronic idiopathic urticaria: a report of two cases. The British Journal of Dermatology. 2001; 145: 340-3.

37. O’Donnell BF, Barr RM, Black AK, Francis DM, Kermani F, Niimi N, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune chronic urticaria. The British Journal of Dermatology. 1998; 138: 101-6.

38. Grattan CE, Francis DM, Slater NG, Barlow RJ, Greaves MW. Plasmapheresis for severe, unremitting, chronic urticaria. Lancet. 1992; 339: 1078-80.

39. Agostoni A, Cicardi M. Drug-induced angioedema without urticaria. Drug Saf. 2001; 24:599-606.

40. Reed LK, Meng J, Joshi GP. Tongue swelling in the recovery room: a case report and discussion of postoperative angioedema. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2006; 18:226-9.

41. Chiu AG, Newkirk KA, Davidson BJ, Burningham AR, Krowiak EJ, Deeb ZE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: a multicenter review and an algorithm for airway management. The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 2001; 110: 834-40.

42. Vleeming W, Van Amsterdam JG, Stricker BH, de Wildt DJ. ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. Incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998; 18: 171-88.

43. Fuchs SA, Meyboom RH, Van Puijenbroek EP, Guchelaar HJ. Use of angiotensin receptor antagonists in patients with ACE inhibitor induced angioedema. Pharm World Sci. 2004; 26: 191-2.

44. Lo KS. Angioedema associated with candesartan. Pharmacotherapy. 2002; 22: 1176-9.

45. Warner KK, Visconti JA, Tschampel MM. Angiotensin II receptor blockers in patients with ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2000; 34: 526-8.

46. Howes LG, Tran D. Can angiotensin receptor antagonists be used safely in patients with previous ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema? Drug Saf. 2002; 25:73-6.

47. Byrd JB, Adam A, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America. 2006; 26: 725-37.

48. Sadeghi N, Panje WR. Life-threatening perioperative angioedema related to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. The Journal of otolaryngology. 1999; 28:354-6.

49. Byrne TJ, Douglas DD, Landis ME, Heppell JP. Isolated visceral angioedema: an underdiagnosed complication of ACE inhibitors? Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2000; 75:1201-4.

50. Dean DE, Schultz DL, Powers RH. Asphyxia due to angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor mediated angioedema of the tongue during the treatment of hypertensive heart disease. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2001; 46:1239-43.

51. Pavletic A. Late angioedema caused by ACE inhibitors underestimated. American Family Physician. 2002; 66:956, 8.

52. Davis AE, 3rd. Mechanism of angioedema in fi rst complement component inhibitor defi ciency. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 2006; 26:633-51.

53. Davis AE, 3rd. The pathophysiology of hereditary angioedema. Clinical Immunology. 2005; 114:3-9.

54. Varga A, Arellano G, Tamayo L, Cardona R. Edema Angioneurótico Hereditario (caso clínico). Revista de Inmunoalergia de la Asociación Colombiana de Alergia, Asma e Inmunología. 2002; 11: 112-5.

55. Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt J. Hereditary angioedema: new fi ndings concerning symptoms, affected organs, and course. The American Journal of Medicine. 2006; 119: 267-74.

56. Frank MM. Hereditary angioedema: a half century of progress. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2004; 114: 626-8.

57. Binkley KE, Davis A, 3rd. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic characterization of a novel estrogen-dependent inherited form of angioedema. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2000; 106: 546-50.

58. Bork K, Barnstedt SE, Koch P, Traupe H. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1-inhibitor activity in women. Lancet. 2000; 356: 213-7.

59. Frank MM. Hereditary angioedema. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2005; 17: 686-9.

60. Baxi S, Dinakar C. Urticaria and angioedema. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 2005; 25:353-67, vii.

61. Bork K, Fischer B, Dewald G. Recurrent episodes of skin angioedema and severe attacks of abdominal pain induced by oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy. The American Journal of Medicine. 2003; 114:294-8.

62. Nogawa N, Sumino H, Ichikawa S, Kumakura H, Takayama Y, Nakamura T., et al. Effect of long-term hormone replacement therapy on angiotensin-converting enzyme activity and bradykinin in postmenopausal women with essential hypertension and normotensive postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2001; 8: 210-5.

63. Proudler AJ, Ahmed AI, Crook D, Fogelman I, Rymer JM, Stevenson JC. Hormone replacement therapy and serum angiotensin-converting-enzyme activity in postmenopausal women. Lancet. 1995; 346: 89-90.

64. Bowen T, Cicardi M, Farkas H, Bork K, Kreuz W, Zingale L., et al. Canadian 2003 International Consensus Algorithm For the Diagnosis, Therapy, and Management of Hereditary Angioedema. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2004; 114: 629-37.

65. Frank MM. Hereditary angioedema: the clinical syndrome and its management in the United States. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 2006; 26:653-68.

66. Zuraw BL. Novel therapies for hereditary angioedema. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 2006; 26: 691-708.

67. Frigas E, Park M. Idiopathic recurrent angioedema. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 2006; 26: 739-51.

68. Pappalardo E, Zingale LC, Cicardi M. Increased expression of C1-inhibitor mRNA in patients with hereditary angioedema treated with Danazol. Immunology letters. 2003; 86: 271-6.

69. Alsenz J, Lambris JD, Bork K, Loos M. Acquired C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) defi ciency type II. Replacement therapy with C1-INH and analysis of patients’ C1-INH and anti-C1-INH autoantibodies. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1989; 83: 1794-9.

70. Cicardi M, Zingale LC, Pappalardo E, Folcioni A, Agostoni A. Autoantibodies and lymphoproliferative diseases in acquired C1-inhibitor defi ciencies. Medicine. 2003; 82: 274-81.

Cómo citar

Descargas

Descargas

Publicado

Cómo citar

Número

Sección

| Estadísticas de artículo | |

|---|---|

| Vistas de resúmenes | |

| Vistas de PDF | |

| Descargas de PDF | |

| Vistas de HTML | |

| Otras vistas | |